NARRATIVE REVIEW

https://doi.org/10.47811/bhj.169

Health in all policies for happiness, wellbeing and health: a narrative review

Karma Tenzin1, Tandin Wangmo2, Kinzang Yangden3, Pem Namgyel4, Gampo Dorji5

1 Faculty of Undergraduate Medicine, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences

2 Ministry of Health, Royal Government of Bhutan

3 Faculty of Nursing and Public Health, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences

4 World Health Organization, South East Asia Regional office, India

5 World health Organization office, Nepal

Corresponding author:

Karma Tenzin

ORCiD : https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9328-2312

ABSTRACT

The pursuit of good health is fundamental to both personal well-being and social progress. The perception of health has advanced to include not only physical well-being but also mental and social dimensions, aligning with the WHO’s definition of health. Similarly, the importance of population health in fostering national development cannot be overstated.

The Health in All Polices (HiAP) framework, endorsed by the WHO, emphasizes the interconnectedness of health with various policy domains. This approach advocates for integrating health considerations into all sectors of governance, including transportation, education and economic planning. By encouraging dialogue and collaboration among diverse sectors, HiAP aims to create healthier environments and generate co-benefits that enhances overall societal well-being.

In the Bhutanese context where the national health policy emphasizes on holistic well-being, implementing HiAP represents a significant positive development. By prioritizing health across various policy domains, Bhutan can further enhance its national philosophy of gross national happiness and well-being.

This review aims to explain the critical apparatuses for successful implementation of HiAP in Bhutan, highlighting the pivotal roles of effective leadership, intersectoral collaboration and policy coherence in promoting happiness, health equity and fostering a healthy society.

Keywords: Bhutan; Health in all policies; happiness; well-being, whole of government approach.

INTRODUCTION

Good health is indispensable for individual well-being and societal prosperity1. The World Health Organization (WHO) asserts that health is a fundamental right for every human being, regardless of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition. Every country in the world is now a party to at least one treaty addressing health-related rights2. Ever since, the value of a healthy population has been emphasized in relation to a productive workforce, a secure nation, and a booming economy2.

Over the decades, understanding of health has evolved from a narrow focus on physical health towards a holistic perspective. This shift is aptly captured by the WHO’s 1948 definition: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition emphasizes that physical health alone, often centered on disease control, does not necessarily equate to being healthy. Instead, mental and social well-being is equally important in fostering a healthy and happy society.

People’s health and well-being are key elements for a nation’s development. To address this, the WHO introduced the concept of Health in All Policies (HiAP). The Helsinki statement on “Health in all Policies” advocates for policymakers to integrate health consdierations into all aspects of governance to enhance people’s wellbeing and foster development3. This approach helps us recognize that health outcomes are not solely the product of health programs but are significantly influenced by policies beyond the health sector.

HiAP promotes strong relationships between the health sector and other sectors, encouraging dialogues that keep health on policy agendas. This not only generates co-benefits, improving outcomes across all involved sectors, but also improves policymaker’s accountability for health impacts at all levels4. By incorporating health considerations into policies related to transport, housing, urban planning, environment, education, agriculture, finance, taxation and economic development, HiAP aims to promote overall health and health equity.

HiAP APPLICATIONS IN BHUTAN

This review aims to capture the essentials elements for the success of HiAP in achieving happiness and holistic well-being in the Bhutanese context by addressing key thematic areas.

Whole of Government approach

The United Nations General Assembly has endorsed strategies promoting a “whole of Government” approach to health and its determinants, underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic’s poignant demonstration of its necessity5. This approach, which integrates governmental and social efforts, is pivotal for synergizing health and well-being agendas6.

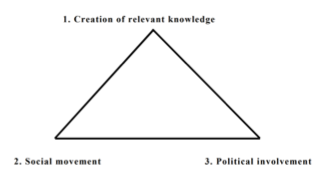

Figure 1: Whole of government approach in health systems7

Model implementations of this approach can be observed in countries like Finland, Thailand and Brazil, where the triangular relations among stakeholders is effectively realized, emphasizing the generation of mutual interests and visible and invisible co-benefits8.

Whole of Government approach in the context of Bhutan

Bhutan has strategically initiated action plans to steer the nation towards a holistic national health agenda. Examples include the Multi Stakeholder Action Plan (MSAP) for the prevention and control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), the National Alcohol Prevention Plan, the Healthy City Action Plan and the Suicide Prevention Plan, among others9-11.

Bhutan stands out as one of the few countries where sectors such as education, environment, human settlements and Civil Society Organizations, have integrated health agendas into national development plans, as evidenced by initiatives like the 13th Five-Year Plan, currently in the draft stage.

NCDs is a rapidly emerging issue in Bhutan, with nearly 40% of adult population having either diabetes or hypertension12. Similarly, the burden of cancer compounds the healthcare landscape, leading to considerable health expenditure, late diagnoses and limited opportunities for reversal13.

Addressing NCDs and cancers dictates a paradigm shift towards a community-based healthcare model, surpassing hospital-centric services. Such an approach will not only improve compliance to treatment but also prevents disease, thereby promoting holistic well-being and health within the population14. To this end, the Ministry of Health, with support from the WHO, has introduced a new initiative called Service with Care and Compassion Initiatives (SCCIs) for the prevention and control of NCDs in all 20 districts.

Moreover, parliamentary resolutions have highlighted issues such as the lack of transportation facilities, which hinder access to healthcare for vulnerable population groups. This underscores the interconnectedness of health and transport infrastructure, further emphasizing the need for an integrated approach to health governance. Additionally, concerns raised by the Parliamentarians’ regarding the need to accelerate the focus of NCDs on “hard-to-reach and unreached population” such as the urban poor and geographically difficult to reach, indicated that more efforts must be designed to control and prevent NCDs15.

Prioritizing mental health for holistic well-being

Health, encompassing physical, mental and social well-being, is central to the Gross National Happiness (GNH) framework. Poor mental health is a critical public issue, with the WHO identifying depression as one of the leading causes of disability, and suicide as the fourth leading cause of death among individuals aged 15-29. Severe mental health conditions often result in premature death due to preventable physical ailments16.

Given that up to 60% of the global population is engaged in the workforce, workplaces significantly influence mental health. Discrimination and inequity based on race, gender, sexuality and other attributes contribute to mental stress, which negatively impacts work performance and productivity16. This stress can also lead to physical health issues like heart disease and gastrointestinal disturbances. To address these issues, the WHO recommends implementing health policies in workplaces.

The importance of implementing health policies in the workplace extends beyond the professional environment and highlights gaps in other areas, such as our education system, which predominantly focuses on physical health while giving limited attention to emotional and mental health. Recognizing the integral role of the mind in maintaining overall health, it is crucial to understanding mental processes. This understanding enhances human relationships and personal well-being and influences broader environmental health, a concept known as planetary health. Thus, prioritizing mental health is essential for both individual and societal flourishing17.

To comprehensively prioritize mental health in all areas, Bhutan could enhance its effort in creating work environments that focus on holistic well-being, which is currently lacking. This could involve establishing meditation centers, common staff rooms, recreational facilities and healthy food systems, among other initiatives.

Fostering community resilience

Community assets and community resilience are integral components of the GNH framework. These are crucial for addressing social challenges as well as enhancing wellbeing and public health. Grassroots leadership play a key role in fostering social growth and advancing social justice. Government must enforce laws addressing issues such as gender-based violence and underage alcohol sales, to strengthen community unity.

In Bhutan, organizations like Respect, Education, Nurture, Empower Women (RENEW) offer essential emergency integrated services for survivors of domestic and gender-based violence, with the aim of fostering a just, equitable and happy society. Bhutan’s commitment to international instruments is demonstrated through its ratification of numerous agreements, including the Domestic Violence Prevention Act 2013 and the Child Care and Protection Act 2011, further emphasizing its commitment to the rights of children and women.

Nonetheless, challenges do persist across various levels. Individual obstacles include lack of literacy about rights, victims’ reluctance to seek help due to poverty and low self-esteem, and accountability issues hindering assistance efforts. For example, a study on violence against women found that 72.5% of victims never sought help from anyone. Only 41% confided in their friends, 27.8% told their parents, and merely 7.3% informed a local leader. Only 4.5% sought assistance from an NGO or women’s organization18.

Furthermore, at the community level, challenges persist, including limited access to services in remote areas, insufficient support for victims of gender-based violence, and security concerns for both community workers and victims. These issues continue to be significant areas of concern, despite the efforts outlines in Bhutan’s GNH framework.

Fostering holistic well-being in our environment and physical spaces

The GNH framework also underscores the significance of the environment and physical surroundings, highlighting their crucial role in fostering happiness, well-being, and holistic health. With the United Nations projections indicating that urban populations will comprise 60% of the global populace by 2050, special attention to these factors become imperative. Bhutan, according to the World Bank, exhibits the highest urbanization rate among South East Asian nations, with 37.8% of its population residing in urban areas as of 2017, a figure projected to rise to 56.8 % by 2047 19.

Urban residents, as revealed by a GNH survey, report higher levels of happiness compared to their rural counterparts, attributed to enhanced access to modern amenities. While taking these modern amenities to remote areas sounds like a solution, it has its own disadvantages. Expansion of urbanization exposes individuals to heightened competition for resources such as housing and space, along with increased exposure to pollution, leading to elevated mental stress and decreased mental well-being. Consequently, this impacts community health and environment quality.

In response to these challenges, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution titled “Happiness towards a holistic definition of development” in 201220. Subsequently, member countries called for a high-level meeting on “wellbeing and happiness; Defining a new economic paradigm” aimed at redefining development paradigms to prioritize holistic happiness and well-being20.

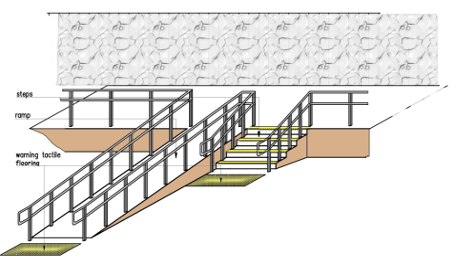

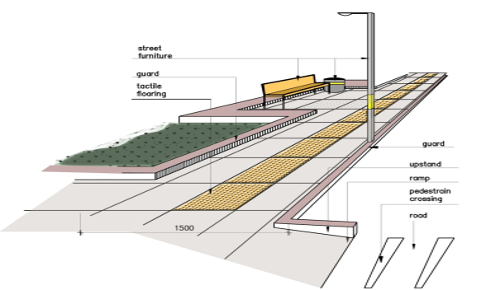

In the pursuit of equitable health outcomes, there is a call for a comprehensive HiAP approach, which acknowledges the diverse health needs of all individuals, including those with disabilities. It is essential to recognize that everyone may experience phases of disability at some point in their lives. Whether it’s due to old age, illness, pregnancy, obesity or temporary injury, individuals may find themselves facing limitations. Bhutan’s guidelines for disability-friendly construction, enshrined in regulations like the Bhutan Building Regulations (BBR) and Building Code of Bhutan (BCB) prioritize inclusive design standards and accessible facilities21.

A B

Figure 2 A: Ramp for wheelchair; B: walking aid for the visually impaired on a walkway