INTRODUCTION

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder, affecting about 1 in 200,000 individuals1. It often presents with massive cervical lymphadenopathy with extra-nodal involvement in up to 40% of cases2. Diagnosis requires clinical suspicion and pathological confirmation. While often self-limiting with favorable prognosis, treatment is reserved for symptomatic or vital-organ involvement2. We present a case of RDD initially misinterpreted as lymphoma on cytology, with confirmation via histopathology. This highlights diagnostic challenges, emphasizing the need for clinical-pathological awareness to prevent overtreatment and proper management of this rare condition. It also outlines cytological pitfalls and key diagnostic clues for accurate RDD identification.

CASE PRESENTATION

Clinical History

A 58-year-old male presented to a regional referral hospital with a painless right sided neck mass that had gradually increased in size over a period of three months. It was associated with intermittent low-grade fever. He denied chronic cough, weight loss, night sweats, voice changes, dysphagia or odynophagia. His past medical and surgical history were unremarkable. He reported a long-standing history of chewing tobacco and drinking alcohol, with occasional beetle nut use. However, he had discontinued these habits three months ago, after noticing the neck lump.

Clinical Examination and Investigations

Examination revealed enlarged bilateral submandibular lymph nodes measuring 1.5 - 2 cm in diameter and a 1.5cm sized right sided level II cervical lymph node. All lymph nodes were firm, non-tender, mobile and had normal overlying skin. There were no palpable axillary or inguinal lymph nodes. Oral examination, nasal endoscopy, and fiber optic laryngoscopy were unremarkable.

Laboratory studies showed an elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) of 86 mm/h, while the complete blood count, renal and liver function tests were all within normal limits. Viral markers were non-reactive (Table 1). The initial neck ultrasound demonstrated multiple oval, hypoechoic lesions in bilateral submandibular and supraclavicular regions, ranging from 1.4*0.9cm to 2.7*1.7cm in size.

Initial Clinical Impression and Diagnostic workup

Since Bhutan is an endemic region for tuberculosis, the initial working diagnosis included tuberculous lymphadenitis or infective lymphadenitis, with reactive lymphadenopathy and lymphoma also considered as part of the differential diagnoses. In accordance with national practice, the patient was started on empirical oral antibiotics but showed no clinical improvement on follow-up.

Subsequently, a fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of the right submandibular lymph node (level IB) was performed at the regional referral hospital. Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining of the aspirate was negative for acid-fast bacilli. The cytology report revealed the “presence of atypical binucleated cells” raising strong suspicion for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Based on this provisional cytological diagnosis, the patient was referred to the National Referral Hospital where an excisional biopsy of the right submandibular lymph node (level IB) was carried out for definitive evaluation.

Table 1. Summary of laboratory investigations of the 58-year-old man performed at the regional referral hospital.

|

Investigations |

Findings |

Normal limits |

|

CBC |

WBC: 5.6 * 10^3/µL Lymphocyte: 28.50% Neutrophil: 65%. RBC: 4.21 * 10^3/µL hemoglobin: 15.3 g/dL Platelet count: 176,000 * 10^3/µL |

3.61-9.56 * 10^3/µL 18.60-47.50% 39.30-73.00% 4.49-6.19 * 10^3/µL 14.00-18.40 g/dL 138.00-450.00 * 10^3/µL |

|

ESR |

86 mm/hour |

0.00-15.00 mm/hour |

|

LFT |

AST: 43 IU/L ALT:17 IU/L ALP:92 IU/L Total Bilirubin: 1.6mg/dL Direct Bilirubin:0.3mg/dL Indirect Bilirubin: 0.75 mg/dL |

5.00-46.00 IU/L 5.00-49.00 IU/L 40.00-129.00 IU/L 0.00-1.20 mg/dL 0.00-0.40 mg/dL 0.20-0.80 mg/dL |

|

RFT

|

Blood-urea: 11 mg/dL Creatinine: 0.90 mg/dL |

10.00-50.00 mg/dL 0.80-1.30 mg/dL |

|

Serum electrolytes

|

Serum sodium: 138 mg/dL Serum potassium: 4.33 mg/dL Serum chloride: 108 mg/dL |

133.00-146.00 mEq/L 3.80-5.40 mEq/L 96.00-110.00 mEq/L |

|

Viral markers |

Anti-HIV: Non-reactive Anti-HCV: Non-reactive HBsAg: Non-reactive |

Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable |

WBC: white blood cell; RBC: red blood cell; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LFT: liver function test; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; RFT: renal function test; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

Pathological Evaluation of the Excised Lymph Node

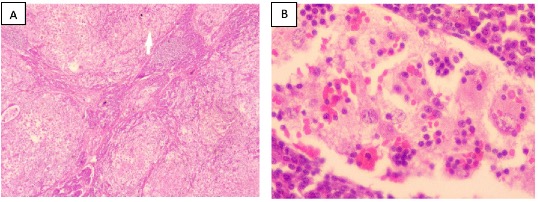

Grossly, the lymph node measured 2.5x2x1.5 cm and had an inhomogeneous tan-white cut surface. Microscopic examination revealed an enlarged lymph node with distended sinuses containing a prominent population of histiocytes, characterized by enlarged round nuclei and voluminous cytoplasm exhibiting emperipolesis with engulfment of lymphocytes (Figure 1 A-B). The lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the parenchyma of the lymph node was not remarkable cytologically. Scattered lymphoid follicles displayed atrophic germinal centers.

Fig 1. Microscopic images (hematoxylin and eosin, H&E-stained slides) of an excised right submandibular lymph node from a 58-year-old man at JDWNRH. (A). A low-power image showing distended sinuses containing a prominent population of histiocytes (40x). (B). High-power image showing emperipolesis (400x).

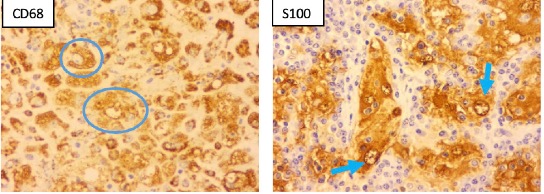

Immunohistochemistry revealed that the lesional histiocytes were positive for S-100 and CD68, and negative for AE1/AE3, ALK1, CD15 and CD30. CD20 and CD3 showed a normal immune-architecture of B- and T-cells respectively. The ki-67 proliferation index within the histiocytic lesion was approximately 5% (low).

Fig 2. Microscopic images (immuno-stained slides) of an excised right submandibular lymph node from a 58-year-old man at JDWNRH, showing positive staining for CD68 (blue circle) in the lesional histiocytes and emperipolesis highlighted by positive staining for S100 (blue arrow).

Special stains, including Ziehl Neelsen and Grocott Methenamine Silver, showed no microorganisms. GeneXpert was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The final histopathological diagnosis was RDD, given the presence of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy.

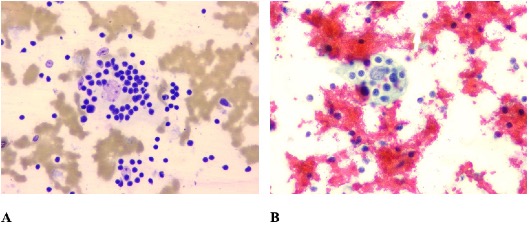

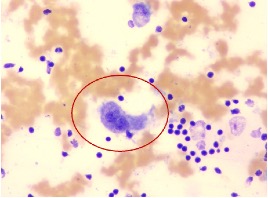

Cytology slides retrieved retrospectively from the regional referral hospital revealed moderately cellular smears composed of histiocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells in a red blood cell rich background. The histiocytes were large with abundant cytoplasm exhibiting emperipolesis of lymphocytes (Figure 3A-B). A few atypical binucleated histiocytes were also noted (Figure 4).

Management and Follow-up

The patient was counselled on the benign and self-limiting nature of the condition and reassured accordingly. He was advised to return for review if the nodes on the neck increased in size, caused pain or any discomfort that might warrant excision. At both the 6-month and 14-month follow-up visits, he did not report any new complains and had no change in size of the neck nodes.

Fig 3. Microscopic images (A. Leishman Giemsa cocktail- and B. Papanicolaou- stained slides) of fine needle aspiration cytology of right submandibular lymph node of a 58-year-old man, showing emperipolesis (400x).

Fig 4. Microscopic images (Leishman Giemsa cocktail-stained slide) of fine needle aspiration cytology of right submandibular lymph node of a 58-year-old man, showing atypical looking binucleated cells (400x).

DISCUSSION

RDD is a rare histiocytic disorder first described by Destombes in 1965 and later characterised by Rosai and Dorfman in 1969 as “sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy”3-5. It predominantly affects children and young adults, with a slight male preponderance, and has an estimated incidence of 100 cases annually in the United States. It is particularly rare in Asian populations5,6.

RDD may occur as an isolated disorder or in association with autoimmune, hereditary, or malignant conditions7. The classical presentation is painless, massive cervical lymphadenopathy, sometimes accompanied by fever2. Approximately 40% of the patients show extra-nodal involvement with skin, soft tissue, breast, central nervous system, and the gastrointestinal tract being affected8,9. RDD is frequently misdiagnosed as lymphoma in clinical settings and distinguishing it from malignancies requires a heightened level of clinical suspicion.

Diagnosis generally requires tissue biopsy from the affected site, although FNAC can suggest the diagnosis due to its characteristic cytological features10. Histiocytes in RDD are large with abundant pale cytoplasm, vesicular nucleus with evenly distributed chromatin and indistinct nucleoli.

Rarely, binucleated and multinucleated atypical histocytes may appear and mimic malignancy11. In our case, such atypical cells led to an initial suspicion of Hodgkin lymphoma on cytology. This aligns with reports that FNAC has lower diagnostic accuracy in lymphoproliferative disorders, and that the misdiagnosis rates for RDD can be as high as 12% in lymph node aspirations and 50% in extranodal aspirations12,13. Nonetheless, FNAC has higher diagnostic accuracy for reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, infectious diseases, granulomatous and metastatic tumors.

Histopathological evaluation is essential for accurate diagnosis. The characteristic histology of RDD includes a disrupted nodular architecture with significant dilatation of lymphatic sinuses, partial disruption of follicles and germinal centers, along with capsular and pericapsular fibrosis. The lymphatic sinuses are distended with lesional histiocytes with phagocytized lymphocytes or plasma cells, a phenomenon known as ‘emperipolesis’. Cytological examination in RDD usually demonstrates emperipolesis, although this key feature can be missed by inexperienced assessors. In our case, retrospective review of cytology slides revealed classic emperipolesis that had been overlooked, likely due to limited familiarity with RDD, a rarely encountered condition in the country. Immunohistochemically, the histiocytes of RDD express CD68 and Lysozyme, but unlike most other histiocytes, they are strong S100 positive10.

Differentiating RDD from lymphoma is crucial because, despite their overlapping clinical features, the treatment modalities and prognosis differ significantly. Both conditions may show large lymphoid cells on cytology, and an inflammatory or reactive background may further complicate the cytological picture.

Although emperipolesis is a hallmark of RDD, it may be absent or easily overlooked during cytological evaluation. In contrast, Hodgkin lymphoma is characterised by Reed-Sternberg cells, which are large (15-45 micrometer) bi- or multi-nucleated cells with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and abundant amphophilic to slightly basophilic cytoplasm14. While Reed-Sternberg cells are a diagnostic hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma, they can occasionally appear in other benign and malignant conditions, and are often more challenging to recognize in FNAC smears than in tissue histopathological examination14. Given the diagnostic difficulties associated with cytology, immunohistochemistry is essential for confirmation. RDD typically shows S100-positive histocytes, helping distinguish it from CD30-positive cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma. Additional histiocyte/monocyte markers such as CD68, CD4, CD14 and CD163 support the diagnosis of RDD.

While lymphoma requires aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, RDD is often benign and self-limiting. Interventions are reserved for symptomatic or extranodal involvement. Surgery may be considered for localized disease and steroids for systemic disease2. Misdiagnosis can lead to overtreating patients with RDD, exposing them to unnecessary chemotherapy and its associated side effects. Although RDD is considered benign, 30-50% of cases harbour MAPK/ERK pathway mutations, and the World Health Organization has classified it under histiocyte/macrophage neoplasms in its 5th edition of hematolymphoid tumors15.

In our case, the presence of a few binucleated histiocytes and the patient’s history of low-grade fever with multiple cervical lymph nodes led to an initial interpretation of “suspicious for Hodgkin lymphoma”. Excisional biopsy demonstrated features typical of RDD, and immunohistochemistry (S100+) confirmed the diagnosis. Notably, the binucleated histiocytes seen on cytology were rarely observed in histopathological examinations.

This case contributes to the limited regional and global literature on RDD and highlights a diagnostic pitfall in cytology that is significant for pathologists and clinicians in tuberculosis-endemic regions like Bhutan where lymphadenopathy is common. The diagnosis was conclusively established through excisional biopsy and immunohistochemical markers, enhancing the scientific rigor of the report. A 14-month follow-up demonstrated no disease progression, supporting the self-limiting nature of RDD and reinforcing the value of conservative management. The limitation of this report is that molecular studies to identify MAPK/ERK pathway mutations could not be performed due to the lack of such facilities in the department.

CONCLUSION

RDD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy, especially when cytology reveals a mix of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. This case highlights the limitations of relying solely on cytology, as rare conditions like RDD can mimic lymphoma and be easily misinterpreted. A high index of suspicion, supported by timely histopathological assessment and immunohistochemical studies, is essential to ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid unnecessary treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the patient for consenting to publish this case report.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for his anonymized information and images to be published in this article.

REFERENCES

1. Yoshida M, Zoshima T, Hara S, Takahashi Y, Nishioka R, Ito K, et al. Case report: Rosai-Dorfman disease with rare extranodal lesions in the pelvis, heart, liver and skin. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1083500. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

2. Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, Kubal T. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21(4):322–7. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

3. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87(1):63–70. [PubMed]

4. Destombes P. [Adenitis with lipid excess, in children or young adults, seen in the Antilles and in Mali. (4 cases)]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1965;58(6):1169–75. [PubMed]

5. Bruce-Brand C, Schneider JW, Schubert P. Rosai-Dorfman disease: an overview. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73(11):697–705. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

6. Rodrigues DOW, Diniz RW, Dentz LC, Costa M de A, Lopes RH, Suassuna LF, et al. Case Study: Rosai-Dorfman Disease and Its Multifaceted Aspects. J Blood Med. 2024;15:123–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

7. Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, Krenova Z, Jaffe R, Emile JF, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood. 2018;131(26):2877–90. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

8. Noguchi S, Yatera K, Shimajiri S, Inoue N, Nagata S, Nishida C, et al. Intrathoracic Rosai-Dorfman disease with spontaneous remission: a clinical report and a review of the literature. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;227(3):231–5. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

9. Deen IU, Chittal A, Badro N, Jones R, Haas C. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman Disease- a Review of Diagnostic Testing and Management. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2022;12(2):18–22. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

10.Rajyalakshmi R, Akhtar M, Swathi Y, Chakravarthi R, Bhaskara Reddy J, Beulah Priscilla M. Cytological Diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman Disease: A Study of Twelve Cases with Emphasis on Diagnostic Challenges. J Cytol. 2020;37(1):46–52. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

11.Garza-Guajardo R, García-Labastida LE, Rodríguez-Sánchez IP, Gómez-Macías GS, Delgado-Enciso I, Chaparro MMS, et al. Cytological diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease: A case report and revision of the literature. Biomed Rep. 2017;6(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

12.Ha HJ, Lee J, Kim DY, Kim JS, Shin MS, Noh I, et al. Utility and Limitations of Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology in the Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;13(4):728. [PubMed] [FullText] [DOI]

13.Shi Y, Griffin AC, Zhang PJ, Palmer JN, Gupta P. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman Disease): A case report and review of 49 cases with fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytojournal. 2011;8:3. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

14.Parente P, Zanelli M, Sanguedolce F, Mastracci L, Graziano P. Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg-Like Cells in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;10(12):1019. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

15.Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms.Leukemia.2022;36(7):1703–19. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]